“The yellow glistens.

It glistens with various yellows,

Citrons, oranges and greens

Flowering over the skin.”

Wallace Stevens

My mother always liked me in yellow, a color that left me decidedly unmoved. I remember owning a bright one-piece suit, a pair of Bermuda shorts (I had sneakers to match those shorts unfortunately) and a poplin shift—all in yellow. When I was 13 I bought a buttercup colored two-piece bathing suit and tried to sneak out in it to the pool. My mother thought it was fine; my father ordered me back upstairs to change. As hard as I fought to grow up, he fought to keep me the same. Even that sweet two-piece was too much for him. I think he knew there was no turning back once I was allowed to wear it. And he was right. Within two years I was out of his grasp, sporting a bikini and cut-offs, falling in love with a boy named Paul, then a boy named Joe. Then both of them at the same time.

My mother wore yellow at my brother Ben’s wedding. She chose the most lovely gown—it was the color of lemon chiffon, and she accessorized it with long white gloves and drop crystal earrings. The simple diamante cord on the dress accented her slim waist. Her understated dress fit to perfection. I know she felt lovely that day, which, after all, is the true purpose and measure of a dress. I remember how happy and proud she was to have her whole family with her. I could see how special she felt as she was escorted down the aisle to her seat, confident and excited.

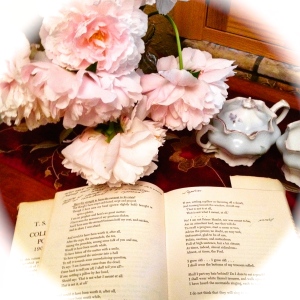

We always gave my mother yellow flowers and bouquets. She adored big mums and daisies, roses, carnations and lilies—dressed with purple for spring, burgundy and russet for fall. She liked simple flowers too. Wherever we lived, my father planted marigolds and daffodils somewhere in the yard. She delighted in tulips and violas, the small faced pansies and the big bearded irises. She loved to watch the seasons change and the gardens bloom.

My mother always wanted to own her own home. We had moved so much she had grown accustomed to packing up and not getting attached. After my dad died, she pretty much gave up on the idea that she’d ever own a home again. Then, in 1995, 20 years ago this month, everything changed. Mom and I were running errands, as we did every Saturday afternoon, when we saw an open house and decided to go in. It was a pretty day and we were having fun. The sweet old house had everything we loved: a built in china hutch and a fireplace with bookcases on either side; hardwood floors, a bay window. We were standing in the kitchen when the listing agent started talking to us. We couldn’t keep the ruse up—we confessed right away that we were just looking. She asked lots of questions and we opened up to her. We told her about our circumstances—that mom was a 73-year-old widow working full-time to provide for herself and her disabled son—that I could help, but we didn’t own anything. The agent really listened. When we finished, she said, “If I could find a home for you, would you be interested?” We looked at each other and said, “Of course!”

Our agent’s name was Donna, and she found a bank that gave home loans to buyers with disabled family members. We pre-qualified for a modest amount and set out looking. There wasn’t a lot to see. We were all just on the verge of getting discouraged when my husband and I found a perfect little stucco house with an enormous elm tree in the front yard. It had a new kitchen and hardwoods, a large yard and a driveway. It faced west and was close to everything. And it became mom’s first home.

The first thing we did after mom got the house was paint it. And, of course, we chose yellow. A yellow like creamery butter, accented with sage trim. The little house looked sweet all iced up. We added yellow and green variagated privet hedges and bright barbary bushes along the porch. My brother planted yellow and purple iris down the side of the drive. Some he bought; some he dug up from his old garden. Eventually, we even painted the kitchen yellow in an homage to Provence. A couple of years later, when my husband and I bought our first home, I gave mom the corner hutch from my dining room. We lined the walls of her reading room with bookcases and made sure she had a comfy recliner to rest in after a long day at work.

My mother worked until she was 82. One day she arrived at the office to find men carrying out office furniture—including her desk. The business had been closed, but no one had told the employees. Mom looked for other work as a bookkeeper, but every time she was called in for an interview and they saw how old she was, the position disappeared. Reluctantly, she retired to her books and her recliner and her puzzles. Her health declined as did my brother’s. And the little yellow house became harder and harder to keep.

This story doesn’t have a happy ending. My brother died just days before Mother’s Day and my mother gave up. She was inconsolable. Her little yellow house had become a cage. She died in March, a week before my birthday, outliving her son by months, but not by choice. And then the little yellow house was gone too, back to the bank. I could not save it anymore than I could save my family. That was how 2012 and 2013 went.

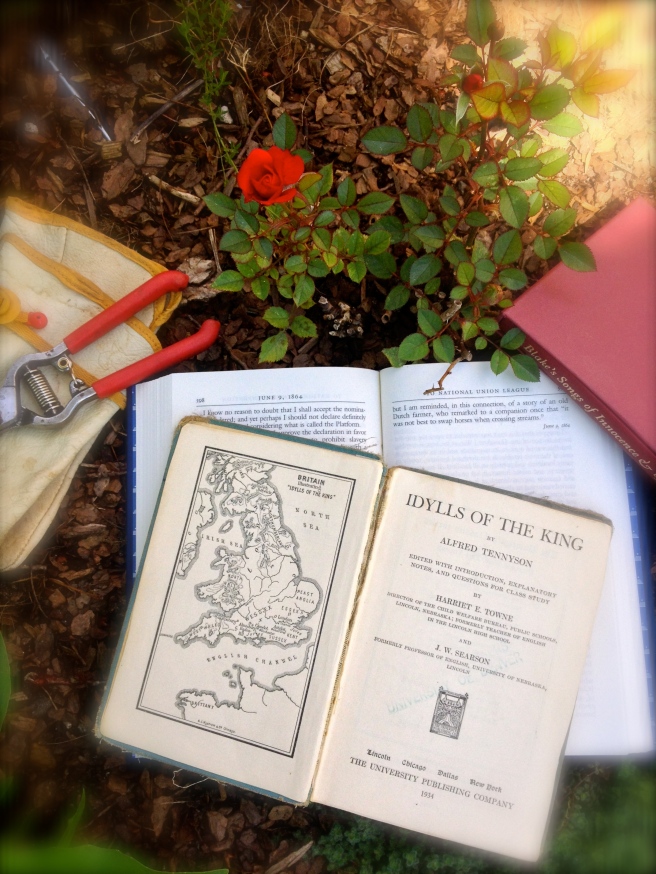

After my mother died, my husband dug up the last remaining iris and brought it to our house. When he planted it, I couldn’t even tell you what color it was. It didn’t bloom the following spring, but the strong stalks gave me comfort. A few weeks ago, we saw it was budding. Weather took one of the stalks, but the other one stood tall. And then, this week, it bloomed for the first time. It bloomed yellow. Yellow like Van Gogh and Kansas, yellow like my crazy old kitchen sink, yellow like a mother’s love. It’s been two years since I last gave my mother flowers. This year, she gave me one. This year, my mother again shines in yellow.